Reading scientific journals is useful not only for keeping up with the latest scientific discoveries and findings, but also to understand that science is more than the facts we see in textbooks. This blog discusses the history of scientific journals, characteristics of different forms of articles, steps for publishing an article and more!

AUG 29, 2020 | By Snehal Kadam, Zill-e-Anam

Scientific journals are publications that circulate and announce discoveries and inventions, gathering known as well as new knowledge in different areas of science. Generally, journal issues are published online and/or offline regularly or ‘periodically’. In this blog, we discuss the relevance, history, characteristics of various publishing forms of scientific journals and steps for publishing an article. Finally, we put forward some new and engaging scientific journals and magazines disseminating science across languages.

The usefulness of scientific journals:

Research in all areas of science helps understand the world around us and discover solutions for problems that exist. However, any research carried out can be useful only if it is communicated to other scientists and the world. Now imagine that, through your research, you have learned something new about the world. How will you tell the world about it? By word of mouth or by writing?

A written text/document in a global language is a better means of communication. It will serve as a knowledge source or starting point for researchers around the world who are interested in your findings and want to know the “What? Why? How? So what?" of your research. Writing in a language known to most of the world enhances the ease of communication and understanding, removing cultural and language barriers between scientists and helping them interact better, through the language of science. Apart from this, publishing in journals also aids in teamwork or ‘collaboration’ between scientists from different corners of the world.

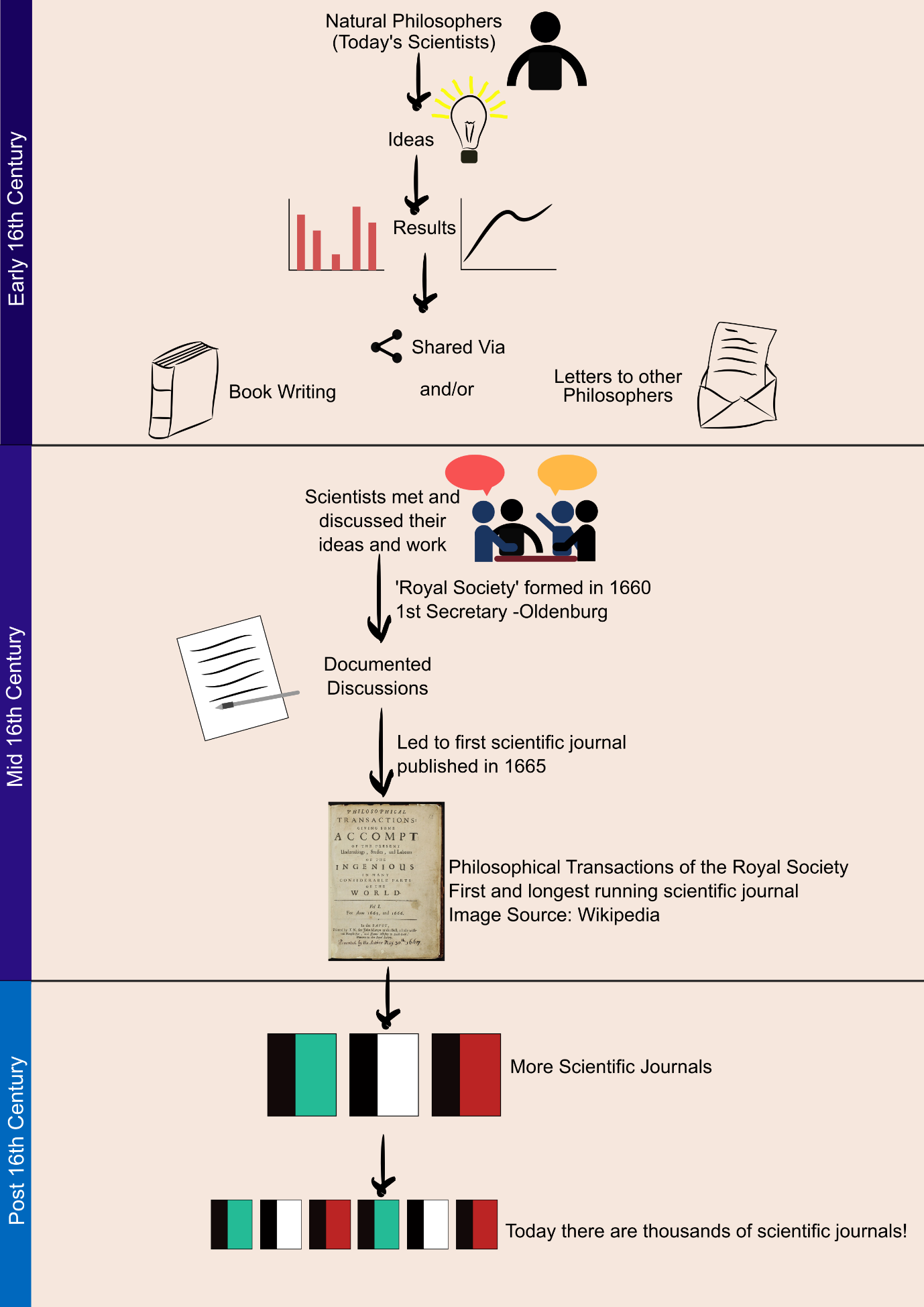

Yesteryears of scientific journals:

In the early 16th century, before scientific journals emerged, there were, many other modes of communicating scientific information. Among these modes, the primary position was held by correspondence. While published books remained a major form of communication, the scientific article made its first appearance during the seventeenth century, in the form of 'letters'. These were not personal messages to friends or colleagues, but an essay-like article written in the form of 'letter or correspondence', reporting the recent experiments and observations. Through letters and correspondences, scientists were able to discuss ideas that were still under the development. Like the modern-day pre-publication, scientists could circulate and share their ideas through letters and obtain critical comments before they finally put them into print.

As the pace of discoveries and inventions accelerated, during Renaissance Europe, correspondence played an essential role in establishing disputes about the priority in the conflicting claims made by two or more researchers. For example, although Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was the first to publish the books, Isaac Newton laid claim to the invention of the calculus, based on his letters that dated much earlier than the publication of Leibniz.

Letters sent to others were shared in many ways. They were read at meetings of societies or social gatherings such as coffee houses & salons. They were copied and forwarded in their entirety or extracts were communicated to other scholars. Correspondence, therefore, held an essential place in the dissemination of scientific information in early modern science. The reason why many scientific periodicals have terms like "letters," "'correspondence," and their cognates in the title is rooted in this history.

To disseminate the information in these learned letters more efficiently, some of the scholars in the seventeenth century voluntarily took the job of making copies and sending it to other scholars. John Collins (1625-83) called the "the scientific gazette” of his time and 'intelligencer' for the Royal Society, was one such person. Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637) and Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) are essential names from France and Italy, respectively. Such scholars received letters, made copies and passed them on to other interested scholars until the emergence of 'scientific societies', which then on took the job of "trafficker in intelligence" in a more formalized manner.

‘Philosophical Transactions’ established in 1665 by Henry Oldenburg (1633-77), is touted to be the first 'scientific journal'. Oldenburg collected, edited and published 'letters' and 'correspondences' received from various scholars addressed to him. Thomas Bartholin (1616-80) took a similar step. He published the collection of the letters in Amsterdam in 1654 with the title ‘Epistolarum anatomicorum rariorum’. Later, he also added letters from other scholars to the compilation. These efforts resulted in the publication of the periodical 'Acta Medica et philosophical Hafniensis', which appeared in Copenhagen from 1673 to 1680.

The circulation of correspondence resulted in societies becoming a platform for critical appraisal, and the periodical publications for wider dissemination slowly crystallized into agencies. For example, the "Bureau d'Adresse" established by the French physician Theophraste Renaudot (1584-1653), organized a series of seminars and brought out a publication Conferences du Bureau d'Adresse from 1634 to 1642. Soon, Journal des sçavans was started in January 1665 by Denis de Sallo in France with weekly book reviews and news in science, as well as in law and theology.

Till today, 'letters' and 'correspondence' form an important means of communicating research.

‘Philosophical Transactions' happens to be the longest-running scientific journal of the world. Starting from the first journal in which the editor had the sole power to decide if the research was suitable for publication, decision-making power shifted slowly into the hands of decision-making committees and has now changed to discipline-based advisory editors.

Story of publishing in scientific journals:

Getting science published is a rigorous process. It all begins with reading about available information in a particular field, and finding an 'unknown' or 'research question' that one wants to try to answer. This research question identifies a gap in the current knowledge or a problem to address. Nowadays, this is done mainly by reading already published papers online in various scientific journals. This is also called 'literature review.' After this, multiple experiments are designed, keeping in mind the research questions. Researchers then carry out the experiments planned in order to address and get answers to their question. It is important to remember that researchers need not necessarily carry out the experiments in 'laboratories.' Sometimes, a farm, a field, a forest, or a mountain may be their resource places for experimentation. This is primarily decided by the area and kind of problem one is addressing. Once the scientists perform these experiments, they analyze and quantify their findings or ‘results’. They then proceed to understand these results in the context of the known knowledge in the field.

Once scientists feel that they have something novel or exciting to share with the world, they begin the process of writing a research article to communicate their work. This is done by noting down detailed methods with the help of figures and tables describing what they did, the results obtained and ultimately putting everything in perspective of the area of research. The next step is finding an appropriate journal and submitting the record or ‘manuscript'. The journal editors check if the submitted manuscript meets the necessary quality standards of the journal. If the manuscript passes this, it is sent out for a process called 'peer-review', wherein multiple scientists (2-3 minimum) from that particular research area thoroughly read and scrutinize the manuscript. They check not only how well it is written, but also if it provides all information, if the results are accurate and if the conclusions are linked to the data. In short one of the central aspects the reviewers are to examine is if the evidence adduced to warrant the claims made. They also can suggest additional experiments to the researchers to provide more proof of their hypothesis. Based on the reviewer's comments, scientists receive a decision from the editor and can choose to re-submit their paper to the same or some other journal. After this, once the reviewer comments are adequately addressed, the paper is finally accepted!

During publication, the authors also decide the availability of their paper to all. Papers that are 'open access’ are available freely, without any subscription fees paid to the journal by readers. However, in order to make papers open access, authors are required to pay a publication fee.

What happens after publication? The paper is made available online for everyone to read. Other scientists can then choose to replicate your results or use them to ask their research questions and eventually publish their own paper. In such cases, your paper will get 'cited’.

Research Articles Vs Reviews:

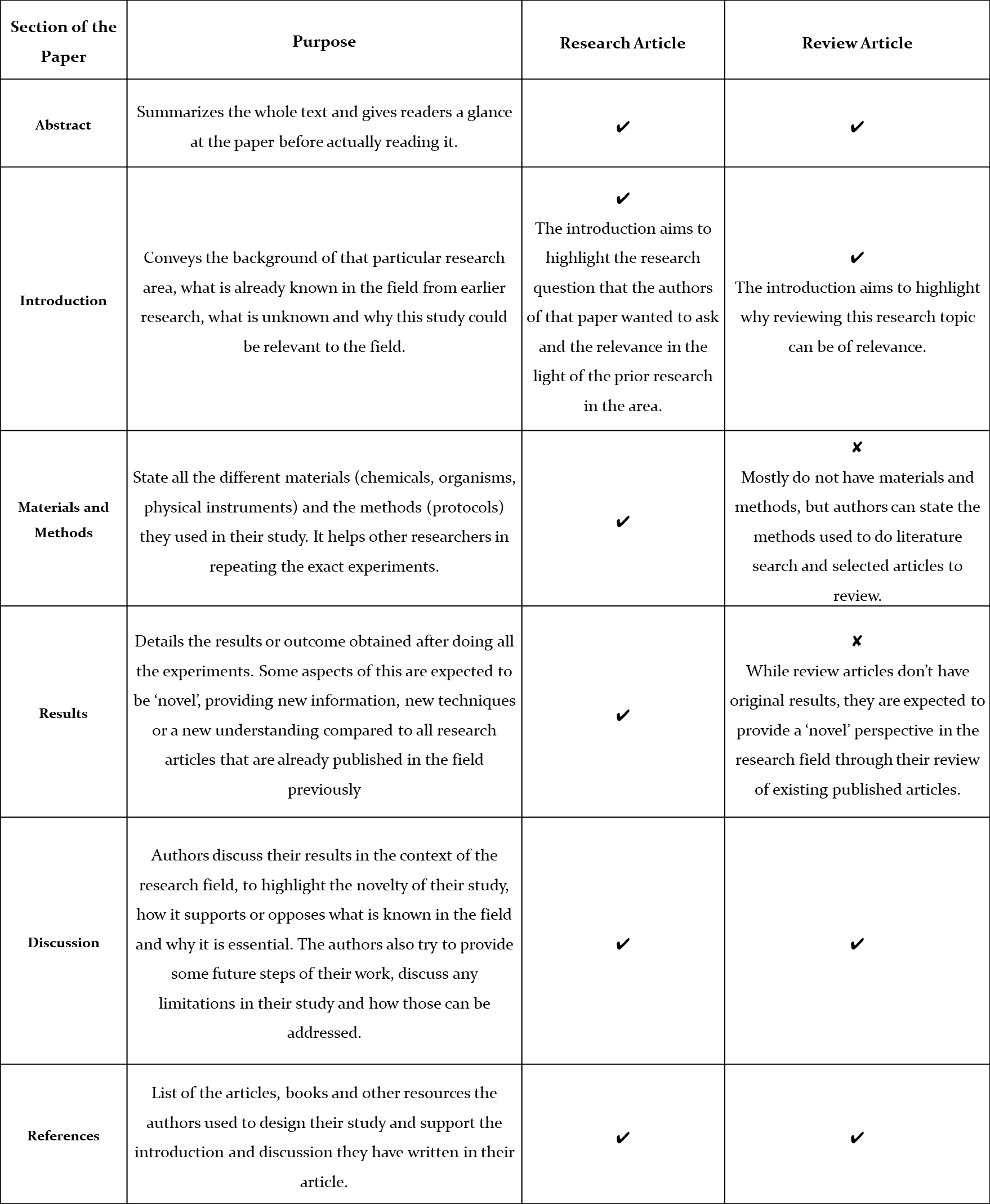

Research articles and reviews are different forms of scientific writings published in journals. A research article is considered a 'primary' source of information or the 'original' study. In other words, it is the first place where the results of a scientific study were reported, along with all the details of the methods used to arrive at those results. (Nowadays a pre-print server also provides advance information, yet, without peer-review, they are not considered as 'valid', until the publication is accepted).

A review article is a 'secondary' source of information, collating research articles related to a particular area of research. This article does not report any new original results obtained by the authors of the review. Instead, the authors’ surveys previously published reports/articles in the field and summarize them to draw broad conclusions or point out new perspectives in the field of study. Analyzing a large amount of known information in the field can help the authors to point out new potential studies to be done in the future that can advance our knowledge, taking the field ahead.

Often research articles provide a reference to review articles in their introduction and discussion sections. Reviews can be written on a wide variety of topics, and this depends on the field and its most recent advances. While review articles are summaries, the authors can bring in their understanding and perspective of the field.

We highlight some basic points of the structures of these two articles in the table below.

Both research articles and reviews are written for a research-specific audience. This means that these articles assume that their readers have some background understanding of research. The language used in these articles is usually filled with many scientific terms (jargon), that a non-researcher may not have come across before. Added to this, many papers have complex data analysis and representation, which may not be the best way to convey information to a non-scientific audience.

Publishing before publishing through pre-prints:

The different steps of publication can make it a very long process until the final article is published online. This leads to a delay in sharing of discoveries and results with the scientific community and the world. While scientists can share work through websites/blogs and social media, these do not serve to give them their due credit. Scientists thus use pre-prints. Pre-prints are articles that have not gone through the peer review process but are publicly available online on a server. Since pre-prints have not been evaluated through the peer review process, there is no guarantee that the study has been designed properly and the manuscript written well. However, there are advantages as well. The scientific community benefits, as they get access to new research faster and free of cost, and the scientists get to share their work and get credit for their novel work even before the peer review process is done.

Journals and magazines for science engagement:

Frontiers For Young Minds is a journal that publishes articles written by scientists for a more general audience, with a focus on children and teens. Scientists write about different topics in science or their research, but in a language that is more accessible to the young audience. This is ensured by allowing young reviewers, children of various age groups, to read the article and give feedback on how readable and accessible the article is before publication, with suggested changes to improve the article.

While dedicated journals such as this are few, many scientific journals have started publishing ‘plain-language summaries’ of the research published in their journal. These are meant to describe the research in a more straightforward language and meant for a broad general audience.

Several science magazines discuss scientific topics and/or the latest scientific discoveries in simpler words than journals. Some of them include Current Science, Science Reporter and Society for Science released in English; Research Matters in Kannada, Marathi, Assamese, Tamil and Hindi, and English; Sandarbh-Eklavya and Vigyan Pragati in Hindi; Safari in Gujrati; Gyan o Bigyan in Bengali; Science ki Duniya in Urdu. This can be an excellent place to start reading about science.

Reading scientific journals is useful for not only keeping up with the latest scientific discoveries and findings, but also to understand that science is more than the facts we see in textbooks. Science is a way of thought, a perspective to critically evaluate the world around us, draw meaningful conclusions from our study of it, and scientific journals are the backbone in this journey.

References:

1. 1667, An introduction to this tract Phil. Trans. R. Soc.11–2 http://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1665.0002

2. https://kids.frontiersin.org/

3. Sarah, S., 2017. Something for everyone. eLife, 6.

Edited by Ratneshwar Thakur and T. V. Venkateshwaran.

Disclaimer:

SciSoup claims no competing interest.

PhD Graduate Student | Special Center for Molecular Medicine | Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.